The Royal Naval Records for Dr. William Todd

Source: "Steele's Navy List from 1723

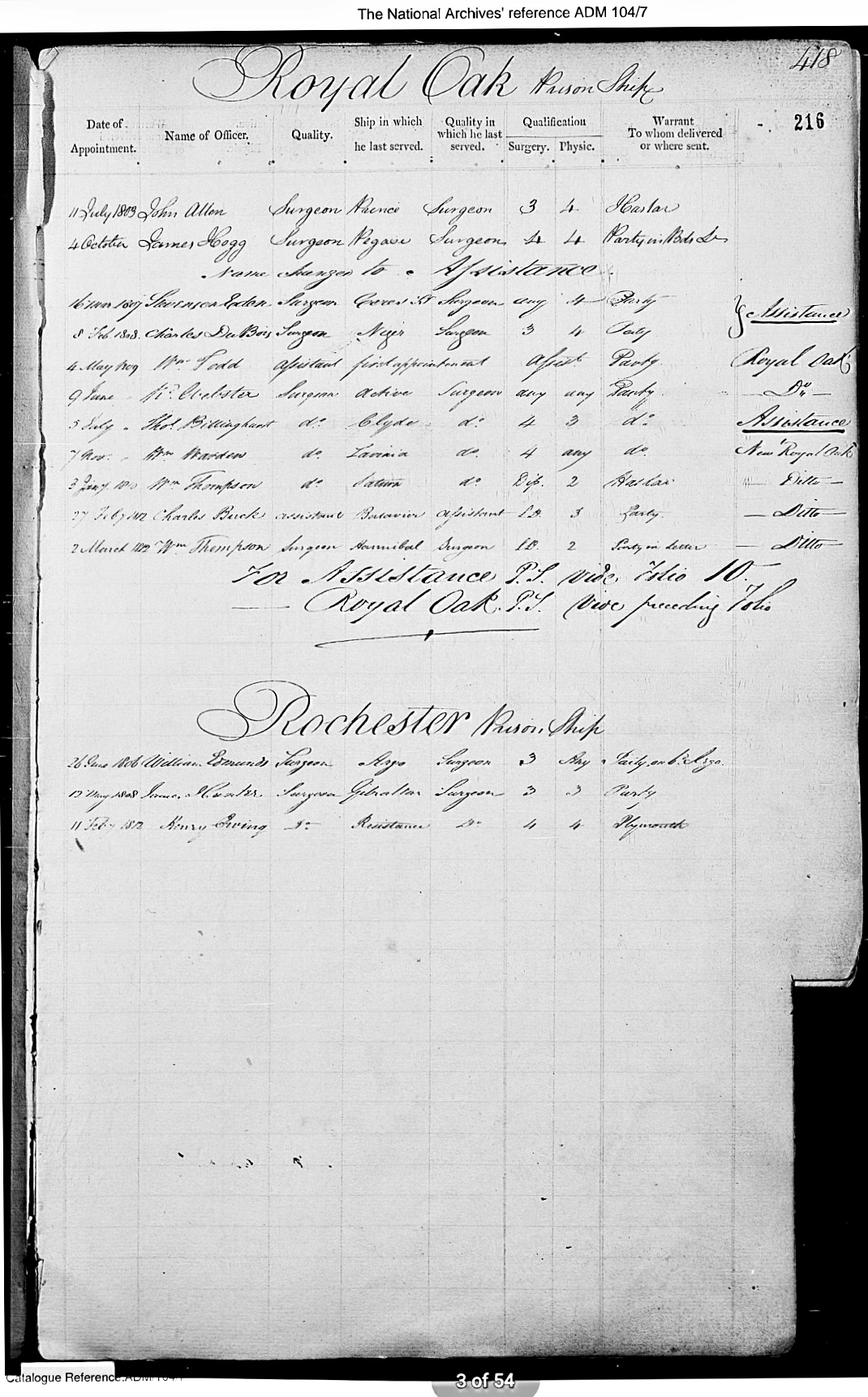

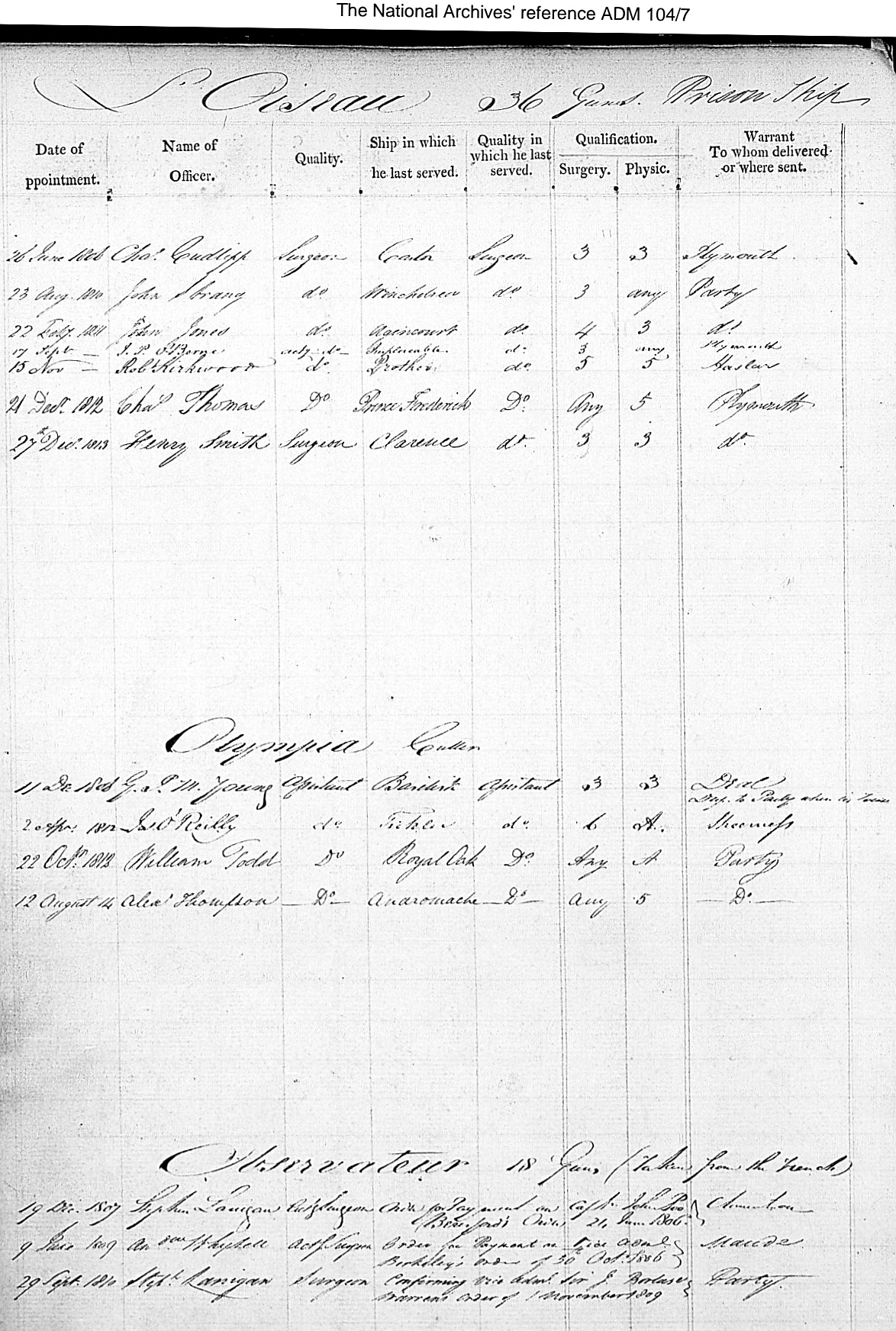

British Naval records in the National Archives and in Steele's Navy List show William Todd serving as Assistant Surgeon in 1809 aboard the HMS Royal Oak #1534 under Captain Lord Beauclerc, Basque Roads, Bay of Bisque, France. This was a Man-of-War Battleship, Third Rate Frigate, 74 cannon, built in 1809. At the time the French navy were threatening British lines of communication in the Iberian Peninsula. A great deal of the British naval effort in the later part of the Napoleonic War (after Trafalgar) was devoted to preventing, by close blockade, the French fleets from leaving harbour. This strategy generally worked, but greatly strained the British men and ships involved, who were stationed there for months on end, often in bad weather.

A second record shows that in January 1812 William Todd serving as Assistant Surgeon onboard the Olympia #1340, a Royal Navy Cutter with 10 Guns/Cannons, serving under Lieutenant W. Windeyer from Downs Station, Kent. The area was a permanent base for warships patrolling the North Sea and a gathering point for refitted or newly built ships coming out of Chatham Dockyard and forming a safe anchorage during heavy weather, protected on the east by the Goodwin Sands.

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, the size of the Royal Navy was reduced from 145,000 troops to 19,000. By 1816, William Todd had begun his lifelong career with the British owned Hudson Bay Company 1816-1851 in Canada.

Nelson and His Navy - Surgery in the Royal Navy

by Tony Harrison, Surgeon, Historical Maritime Society

We are very fortunate in still having access to many surgeons’ journals and reports of the time. These primary documents allow us to listen to the past, first hand, and to fully understand the calibre of these men, certainly as regards their professional skills, but what also speaks to us loudly and very clearly is the sheer humanity and care for their patients extended both to their own side, and their erstwhile enemies. The drunken butchers of myth certainly did exist in the navy of the mid 1750’s but by the turn of the 19th century the surgeon's of the royal navy had earned the respect of their crew's and the gratitude of their country. The success of the Royal Navy during this period and its total mastery of the seas was due in no small measure to the ability of the naval medical department to give the best of current medical care to its seamen.

The general standard of naval surgeons was greatly increased during the latter part of the 18th century. Many of these young men were from north of the border, newly qualified with degrees from the newly established Scottish medical schools of Aberdeen, Glasgow and Edinburgh universities. Lind, Trotter, Robertson and their contemporaries not only raised the standard of medical care to new heights in the navy but also became luminaries in the history of general medicine.

The role of the surgeon on board ship was akin to that of a floating GP. He was responsible for everything medical from childbirth to dentistry. 95% of his time would be taken up with treating the usual ailments and infections consistent with those affecting any group of men living in a tight, closely knit society for months on end. The subject of this article, however, is his surgical skills, usually required during and immediately after action in battle. Considering the conditions under which the naval surgeon performed his operations, either ashore or afloat, as a surgical technician he was unsurpassed. His skill was combined with that knowledge of anatomy and speed of performance, which were vital if the patient were to stand any chance of surviving the degree of shock involved.

Post-operative infection was anticipated as a matter of course, and even in the most successful of cases, suppuration of the affected areas was regarded as quite normal. These wound infections were generally recorded as “inflammation” in the copious records made by the individual surgeons and required by The Sick and Hurt board for inspection on completion of the surgeons tour of duty. Every treatment and operation had to be recorded in minute detail, including the result. If the surgeon was found wanting in medical knowledge or skill, his warrant could be withheld.

The two specific inflammations, dreaded by surgeons were gangrene and particularly, tetanus. Gangrenous tissue was usually cut away, tetanus and its development into lockjaw was however, a different matter. It was generally accepted that lockjaw was more likely to follow wounds in a warm climate.

Naval surgeons found that close fought actions produced less casualties than actions conducted between opposing ships at a distance. In close fought actions, the velocity of cannon balls was so great that that in penetrating the side of a ship a clean aperture was produced, with few splinters. But a spent ball, travelling from a distance usually produced a jagged aperture with numerous deadly splinters by which more men were killed or wounded than by the ball itself. A curious phenomenon was also noted by naval surgeons of the time called “wind of ball”. This injury occurred when a cannon ball, in flight, passed close to any part of the body. It was considered most serious when passing close to the stomach, leaving no obvious marks, but often causing almost instantaneous death. Remarkably, it was also noted that “wind of ball” was never fatal when the ball passed close to the head. Burns and flash burns were also common injuries on the gun deck.

Most naval surgeons had a wide experience of treating fractures, particularly of the extremities, whilst many were well versed in the use of the trephine and the elevation of depressed fractures of the skull, a very common injury in the navy of the time. The most frequent surgical operations to be performed in action were of course amputations of the limbs. It is in the performance of these cases that the naval surgeon of the time was perhaps seen at its best. When it is considered that they were performed without anesthetics, and that post-operative infection was accepted as a matter of course, the successes, which were achieved, can only be viewed as remarkable to the 21st century mind.